Berry Picking Time

The blueberries and blackberries are ready for picking.

We are open 7 days a week 7:00 am to 8:00 pm or earlier or later if you call us to make special arrangements.

We have picnic tables, ice cold water, buckets, gloves and all you need to have a good time. We put your berries in plastic bags after you pick them. A toilet is available in the berry patch and water to wash your hands.

You need to bring a sun hat if desired, containers to take the berries home in if you do not want to keep them in plastic bags. If you are traveling several hours, a cooler with ice is helpful.

Call in advance to check on availability the day your are picking if you are traveling far.

June 10 is a berry Farm to Fork Cooking Class.

We don’t charge for what you eat as you pick!

The berries are larger than every this year. We use

a special natural program to fertilize the plants.

There is no shortage of blueberries this year.

Our berry patch is weed free. We weed trim and do

not use herbicides or insect sprays.

The blackberry crop will be small this year. The hard winter

and the drought have hurt the bramble bushes. We plan on

re-planting most of the patch this winter.

The blackberry patch is a s clean. We hand pull

the weeds and grass to keep it this way.

It's Almost Berry Picking Time

The blueberry bushes are loaded this year.

Non-chemical way to keep the row clean- weed trimming

Blackberry rows are hard to weed under canopy. No weed trimming possible.

Baby Goats Sometime need Help

We have both and at time I wonder the same thing on occasion. Last winter, Eva called me to a hold barn where I found a dead goat under the roof edge. She said she thought the goat took a dive out of the loft door and broke it neck. We lost three goats that week.

This is the time of the year to have baby goats and we have had a bad run of luck with our pigmy goats. Three live and six dead. All of the dead ones came premature for some reason. We have never had that problem.

Yesterday, we found a baby boar goat crying in the paddock and alone. I moved it to where the goats were foraging and no one claimed it. I ran all the goats into a pen and Javier joined me as we checked each female and caught the one that had just delivered. While I took the new mom and hungry baby to a pen, he looked and found the twin of the one we had. Holding the mom by the horns, each got their initial supply of milk. Today we will release her and her babies into a larger confined area, but will keep watch to be sure she continues to care for them.

Not dead, but very hungry

None of the females seemed interested in the baby

What a way to get a drink

Okay now...all is right with the world and each baby has a

place to nurse while Tux stands guard.

Borden Speak

Grave monument epitaph for Gail Borden, Jr

Founder of Borden Milk Company. Borden patented method to make condensed milk in 1856.

No Snakes Under Our Boats

My Morning Chicken and Farm Stuff

I often have my coffee early in the morning just after the sun light creeps through the trees to my east along the road. It is cool and more often than not the newspaper has not been delivered to our mail box. Birds are singing, the barn yard animals are honking and the farm is stretching to wake up. We have bird feeders in the trees in front of the house and during the day small amounts of bird seed fall to the ground. I get great pleasure in seeing my “morning chicken” each day under the feeder eating the spilled grain. She is a Rhode Island Red and stands out against the deep green of the lawn grass. All things are right when she is in her place. She appears not to have a care in the world. I wonder is she is aware of the pleasure she brings.

Life on a farm is very different from having a day job in the city. I live by my lists, both written and remembered. There is no “boss” to tell me what to do. There is also no end to the tasks (that no one but me is going to do) that have to be accomplished every day and that changes over the year as the seasons change.

There are NO annual evaluations with made up lists of what I did right and what areas of improvement I need to focus on. On the farm, we are our own evaluator. Probably more harsh than any former boss I had.

Currently we have baby chicks in brooders that require regular attention to be sure they have feed, water and the right temperature provided by heat lamps. Chicks that arrived a few weeks ago are about ready to move to larger quarters, but with the same standard of care. Another batch arrived 10 days ago and need to stay in the shop for a bit longer. Friday we get yet another box of day old chicks to brood. In time, all will be in our new egg mobile and providing 9-10 dozen eggs a day. These will be real free range chickens living in a cow pasture, so these eggs will be as healthy as you can get with deep yellow yokes.

The last baby calf of the season was born this week, a bull. His mom was a heifer and she waited weeks after all the other girls to get her business done. I suppose she liked the extra attention of our checking her several times a day. Most heifers and cows have their babies without assistance, but she got a little extra help from us. In time, she may have had the baby calf without help, but since we lost too many calves this season we wanted to take no chances. Javier and I pulled a little so the calf would be born with ease. He popped out in Javier’s arms as I pulled his front hoofs. There is a special feeling in the birth of an animal that you participate in.

We took soil samples a few days ago. That entails going over each field and sticking a steel probe in the earth to obtain a one inch sample six inches long. On a 20 acre field, you collect perhaps two quarts of earth. Some years we send many individual samples to see how the minerals are in each paddock. This year we only collected two samples; one from Rocky Branch and one from home. The amount of mineral and nitrogen we use at each place are different. Rocky Branch takes two trucks loads and one at home. This year we will mix Cowboy Bermuda seed with a portion of the mineral and nitrogen and re-plant 35 acres. This is an experiment to see how this forage grass performs. After the seed is distributed we will either drag a tine or run a cultipacker over the ground to set it to germinate. The soil samples let us be exact in determining what minerals and micro nutrients the soil needs.

We do not use Texas A&M’s soil lab except to check nitrogen levels. The method of mineral extraction they use confuses physics. It does not properly evaluate your minerals and how they relate to what you are growing.

We moved a group of male goats off their winter paddock a few weeks ago into an area that we had fenced off from others We wanted to confine the goats in a forest area and not be on pasture. At first, we had two yearling bulls with them, but the bulls escaped by swimming under a fence in the lake to join some cows. They had to be caught and returned to the bull paddock. Around the forest is a barbed wire fence. This week we added three more wires that make it next to impossible for the goats to pass through. They are now confined in the forest, with lots to eat, and will go about their business clearing up the under brush. We laid 400 Ft of water hose to them for water, but will be laying a buried water line soon. We will also build them a shed to stay out of the rain.

We have had rain and the night temperature is approaching 60 degrees, so the grass is starting to respond. It still looks grim for hay production with the number of cattle we graze and the lack of sustained rain. Our number one hay meadow has very light spring grass versus years when we had a large cutting in May. Our current plan is to move 35 cows and their calves onto this field in a week and let them graze it short, then pull them off and fertilize it hoping for rain. If we are lucky, we will get at least one cutting of hay in the early summer. We have already grazed our number two hay meadow, but not yet fertilized it. If we do not have enough grass this year, the cattle get first preference on grass and we will have to buy hay from away and truck it in.

Hopefully in four weeks, we will have a lot of vegetables to sell here at the farm and in farmer’s markets in our area. Our summer vegetables have struggled to get started with the many cool nights we have had, but they are starting to grow. We will be planting more seed this week for some varieties that like warmer day sand nights.

This week we will spend a lot of time in the berry field. We have already weed trimmed under some of the rows, but there are many more to work on. Despite two hail storms, it appears we will have a very good blueberry crop. Blackberries will be lighter this year. We have had a cane virus that killed many of the plants. We replanted in the rows, but those new plants will not produce this year. I expect there will be a need for more replanting this winter. The new plantings of blackberries are doing well. We have irrigation on them and will start fertilization soon. These new blackberries will more than double our production. We expect to have blueberries around Memorial Day or a few day later.

At Rocky Branch, we have a baby fox living in the hay barn. On some days it is laying in the sun staying warm. We only started to have more fox this past year. They are so graceful as they fun when spotted. Of course, at home I think fox were in part responsible for the loss of 60 chickens last winter.

Beside baby calves, we have several baby goats in the old barn now. Unfortunately we have lost more than we had born live. For some odd reason the goats delivered premature this year. I have no idea why this happened. The Spanish/Boar goats have not yet delivered.

The next major project is to trench and lay about 2,000 Ft or more of water line at home. This will allow us to rotation graze here and also be the water source for our egg mobile.

Coffee is finished. I had bacon and eggs on the veranda. Now it is time to go to work. I am running way late today. It is already 8:45 AM, but its Sunday too.

What a life!

What’s not to love.....

Happy Mother’s Day

Food: Six Thingsto Feel Good About

We work very hard on our farm to bring to market fresh fruit, blueberries & blackberries, vegetables and grass-fed beef. Our farm is where “local” hits the road. We are it and we are here near you.

We will never be big enough to sell to Wal-Mart or McDonalds, but we do offer you the very best in what can be produced on a smaller scale.

We feel good about these six points too.

March 22, 2011

Food: Six Things to Feel Good About

By MARK BITTMAN

The New York Times

Mark Bittman on food and all things related.

The great American writer, thinker and farmer Wendell Berry recently said, “You can’t be a critic by simply being a griper . . . One has also to . . . search out the examples of good work.”

I’ve griped for weeks, and no doubt I’ll get back to it, but there are bright spots on our food landscape, hopeful trends, even movements, of which we can be proud. Here are six examples.

• Not just awareness, but power | Everyone talks about food policy, but as advocates of change become more politically potent we’re finally seeing more done about it. Late last year, public pressure enabled the federal government to reauthorize the Child Nutrition Act, which will improve school food, and the Food Safety Modernization Act, which will make food safer. (Gripe alert: Neither is perfect, and it’s easy to be critical of both — the child nutrition bill, for example, may be partially funded by a cut to food stamps — but they mark real progress and increase the possibility of further reform.) Combined with increasingly empowered consumers and a burgeoning food movement (one that Time magazine’s Bryan Walsh suggests has the potential to surpass and save the environmental movement), guarded optimism is called for, especially with the farm bill up for renewal in 2012. If the good guys fail to make some real gains there I’ll be surprised.

• Moving beyond greenwashing | Michelle Obama’s recent alliance with Wal-Mart made even more headlines than the retailer’s plan to re-regionalize its food distribution network, which is if anything more significant. The world’s biggest retailer pledged to “double sales of locally sourced produce,” reduce in-store food waste, work with farmers on crop selection and sustainable practices, and encourage — or is that “force”? — suppliers to reconfigure processed foods into “healthier” forms. (Yes, I think this last is ridiculous, but today I’m all sweetness and light.) Not to be outdone, just last week, McDonald’s made a “Sustainable Land Management Commitment.” We can and should be skeptical of these pronouncements, but the heat that inspired these two giants to promise change may ensure that they follow through. As for the First Lady: “Let’s Move” has helped insert food squarely into the national conversation: everyone from Sarah Palin to Rush Limbaugh to Stephen Colbert talks about it, and even Ms. Palin’s nonsensical comments provoke sensible reactions. And it’s difficult to find a school where someone isn’t gardening.

• Real food is spreading | There are now more than 6,000 farmers markets nationwide — about a 250 percent increase since 1994 (significant: there are half as many as there are domestic McDonald’s), and 900 of them are open during the winter. They’re searchable too, thanks to the USDA. (Community Supported Agriculture programs — CSAs — and food coops are also searchable, courtesy of localharvest.org.) Furthermore, serious and increasing efforts are being made to get that food to the people who really need it: Wholesome Wave, for example, began a voucher program in 2008 that doubles the value of federal food stamps (SNAP) at participating farmers markets; that program has grown more than tenfold in less than three years.

• We’re not just buying, we’re growing | Urban agriculture is on the rise. If you’re smirking, let me remind you that in 1943, 20 million households (three-fifths of the population at that point) grew more than 40 percent of all the vegetables we ate. City governments are catching on, changing zoning codes and policies to make them more ag-friendly, and even planting edible landscaping on city hall properties. Detroit, where the world’s largest urban farm is under development, has warmly and enthusiastically embraced urban agriculture. Other cities, including Pittsburgh, Philadelphia (more on Philly in a week or two), New York, Toronto, Seattle, Syracuse, Milwaukee and many more, have begun efforts to cultivate urban farming movements. And if local food, grown ethically, can become more popular and widespread, and can help in the greening of cities — well, what’s wrong with that?

• Farming is becoming hip | The number of farms is at last increasing, although it’s no secret that farmers are an endangered species: the average age of the principal operator on farms in the United States is 57. Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack recently noted that our farmers are “aging at a rapid rate,” and when he asked, “Who’s going to replace those folks?” it wasn’t a rhetorical question. But efforts by nonprofits like the eagerly awaited FoodCorps and The Greenhorns, both of which aim to introduce farming to a new generation of young people, are giving farming a new cachet of cool. Meanwhile, the Nebraska-based Land Link program matches beginning farmers and ranchers with retirees so that the newbies gain the skills (and land) they need.

• The edible school lunch | The school lunch may have more potential positive influences than anything else, and we’re beginning to see it realized. The previously mentioned child-nutrition bill sets better nutrition standards for school meals and vending machines and increases the number of students eligible for free or reduced-price meals. U.S.D.A. is also behind the “Chefs Move to Schools” program, which enlists culinary professionals to help revamp nutrition curricula and the food itself; around 550 schools are participating. Independent of the Feds, many chefs have been moving to schools on their own. Bill Telepan’s Wellness in the Schools, for example, is working with public schools in New York City, while “renegade lunch lady” Ann Cooper, who remade Berkeley’s school lunch, is taking on the much more challenging program in Boulder, and succeeding. There are scores of other examples, and we’re finally seeing schools rethinking the model of how their food is sourced, cooked and served, while getting kids to eat vegetables. That’s good work.

Of the 1%, by the 1%, for the 1%

| This article has nothing to do with farming except that most if not all farmers are probably not in the 1%. Everyone I know is either out of a job, has a job but is scated they will lose it, or working harder than normal to keep the job they have. All the while they are losing ground economically and having great difficulty making ends meet. In farming, you have very little control over the prices you get and have zero control over the price you pay for fuel, supplies, seed and everything else to farm. This article is very eye opening about the wide split in this country between those that have it all and those that do not. Here in Texas, the Legislature this year is working very hard to be sure the 1% keep all of theirs while the rest of us congtribute and give up so they can have it. |

INEQUALITY

Of the 1%, by the 1%, for the 1%

Americans have been watching protests against oppressive regimes that concentrate massive wealth in the hands of an elite few. Yet in our own democracy, 1 percent of the people take nearly a quarter of the nation’s income—an inequality even the wealthy will come to regret.

BY JOSEPH E. STIGLITZ•ILLUSTRATION BY STEPHEN DOYLE

MAY 2011

THE FAT AND THE FURIOUS The top 1 percent may have the best houses, educations, and lifestyles, says the author, but “their fate is bound up with how the other 99 percent live.”

It’s no use pretending that what has obviously happened has not in fact happened. The upper 1 percent of Americans are now taking in nearly a quarter of the nation’s income every year. In terms of wealth rather than income, the top 1 percent control 40 percent. Their lot in life has improved considerably. Twenty-five years ago, the corresponding figures were 12 percent and 33 percent. One response might be to celebrate the ingenuity and drive that brought good fortune to these people, and to contend that a rising tide lifts all boats. That response would be misguided. While the top 1 percent have seen their incomes rise 18 percent over the past decade, those in the middle have actually seen their incomes fall. For men with only high-school degrees, the decline has been precipitous—12 percent in the last quarter-century alone. All the growth in recent decades—and more—has gone to those at the top. In terms of income equality, America lags behind any country in the old, ossified Europe that President George W. Bush used to deride. Among our closest counterparts are Russia with its oligarchs and Iran. While many of the old centers of inequality in Latin America, such as Brazil, have been striving in recent years, rather successfully, to improve the plight of the poor and reduce gaps in income, America has allowed inequality to grow.

Economists long ago tried to justify the vast inequalities that seemed so troubling in the mid-19th century—inequalities that are but a pale shadow of what we are seeing in America today. The justification they came up with was called “marginal-productivity theory.” In a nutshell, this theory associated higher incomes with higher productivity and a greater contribution to society. It is a theory that has always been cherished by the rich. Evidence for its validity, however, remains thin. The corporate executives who helped bring on the recession of the past three years—whose contribution to our society, and to their own companies, has been massively negative—went on to receive large bonuses. In some cases, companies were so embarrassed about calling such rewards “performance bonuses” that they felt compelled to change the name to “retention bonuses” (even if the only thing being retained was bad performance). Those who have contributed great positive innovations to our society, from the pioneers of genetic understanding to the pioneers of the Information Age, have received a pittance compared with those responsible for the financial innovations that brought our global economy to the brink of ruin.

Some people look at income inequality and shrug their shoulders. So what if this person gains and that person loses? What matters, they argue, is not how the pie is divided but the size of the pie. That argument is fundamentally wrong. An economy in which most citizens are doing worse year after year—an economy like America’s—is not likely to do well over the long haul. There are several reasons for this.

First, growing inequality is the flip side of something else: shrinking opportunity. Whenever we diminish equality of opportunity, it means that we are not using some of our most valuable assets—our people—in the most productive way possible. Second, many of the distortions that lead to inequality—such as those associated with monopoly power and preferential tax treatment for special interests—undermine the efficiency of the economy. This new inequality goes on to create new distortions, undermining efficiency even further. To give just one example, far too many of our most talented young people, seeing the astronomical rewards, have gone into finance rather than into fields that would lead to a more productive and healthy economy.

Third, and perhaps most important, a modern economy requires “collective action”—it needs government to invest in infrastructure, education, and technology. The United States and the world have benefited greatly from government-sponsored research that led to the Internet, to advances in public health, and so on. But America has long suffered from an under-investment in infrastructure (look at the condition of our highways and bridges, our railroads and airports), in basic research, and in education at all levels. Further cutbacks in these areas lie ahead.

None of this should come as a surprise—it is simply what happens when a society’s wealth distribution becomes lopsided. The more divided a society becomes in terms of wealth, the more reluctant the wealthy become to spend money on common needs. The rich don’t need to rely on government for parks or education or medical care or personal security—they can buy all these things for themselves. In the process, they become more distant from ordinary people, losing whatever empathy they may once have had. They also worry about strong government—one that could use its powers to adjust the balance, take some of their wealth, and invest it for the common good. The top 1 percent may complain about the kind of government we have in America, but in truth they like it just fine: too gridlocked to re-distribute, too divided to do anything but lower taxes.

Economists are not sure how to fully explain the growing inequality in America. The ordinary dynamics of supply and demand have certainly played a role: laborsaving technologies have reduced the demand for many “good” middle-class, blue-collar jobs. Globalization has created a worldwide marketplace, pitting expensive unskilled workers in America against cheap unskilled workers overseas. Social changes have also played a role—for instance, the decline of unions, which once represented a third of American workers and now represent about 12 percent.

But one big part of the reason we have so much inequality is that the top 1 percent want it that way. The most obvious example involves tax policy. Lowering tax rates on capital gains, which is how the rich receive a large portion of their income, has given the wealthiest Americans close to a free ride. Monopolies and near monopolies have always been a source of economic power—from John D. Rockefeller at the beginning of the last century to Bill Gates at the end. Lax enforcement of anti-trust laws, especially during Republican administrations, has been a godsend to the top 1 percent. Much of today’s inequality is due to manipulation of the financial system, enabled by changes in the rules that have been bought and paid for by the financial industry itself—one of its best investments ever. The government lent money to financial institutions at close to 0 percent interest and provided generous bailouts on favorable terms when all else failed. Regulators turned a blind eye to a lack of transparency and to conflicts of interest.

When you look at the sheer volume of wealth controlled by the top 1 percent in this country, it’s tempting to see our growing inequality as a quintessentially American achievement—we started way behind the pack, but now we’re doing inequality on a world-class level. And it looks as if we’ll be building on this achievement for years to come, because what made it possible is self-reinforcing. Wealth begets power, which begets more wealth. During the savings-and-loan scandal of the 1980s—a scandal whose dimensions, by today’s standards, seem almost quaint—the banker Charles Keating was asked by a congressional committee whether the $1.5 million he had spread among a few key elected officials could actually buy influence. “I certainly hope so,” he replied. The Supreme Court, in its recent Citizens United case, has enshrined the right of corporations to buy government, by removing limitations on campaign spending. The personal and the political are today in perfect alignment. Virtually all U.S. senators, and most of the representatives in the House, are members of the top 1 percent when they arrive, are kept in office by money from the top 1 percent, and know that if they serve the top 1 percent well they will be rewarded by the top 1 percent when they leave office. By and large, the key executive-branch policymakers on trade and economic policy also come from the top 1 percent. When pharmaceutical companies receive a trillion-dollar gift—through legislation prohibiting the government, the largest buyer of drugs, from bargaining over price—it should not come as cause for wonder. It should not make jaws drop that a tax bill cannot emerge from Congress unless big tax cuts are put in place for the wealthy. Given the power of the top 1 percent, this is the way you would expect the system to work.

America’s inequality distorts our society in every conceivable way. There is, for one thing, a well-documented lifestyle effect—people outside the top 1 percent increasingly live beyond their means. Trickle-down economics may be a chimera, but trickle-down behaviorism is very real. Inequality massively distorts our foreign policy. The top 1 percent rarely serve in the military—the reality is that the “all-volunteer” army does not pay enough to attract their sons and daughters, and patriotism goes only so far. Plus, the wealthiest class feels no pinch from higher taxes when the nation goes to war: borrowed money will pay for all that. Foreign policy, by definition, is about the balancing of national interests and national resources. With the top 1 percent in charge, and paying no price, the notion of balance and restraint goes out the window. There is no limit to the adventures we can undertake; corporations and contractors stand only to gain. The rules of economic globalization are likewise designed to benefit the rich: they encourage competition among countries for business, which drives down taxes on corporations, weakens health and environmental protections, and undermines what used to be viewed as the “core” labor rights, which include the right to collective bargaining. Imagine what the world might look like if the rules were designed instead to encourage competition among countries for workers. Governments would compete in providing economic security, low taxes on ordinary wage earners, good education, and a clean environment—things workers care about. But the top 1 percent don’t need to care.

Or, more accurately, they think they don’t. Of all the costs imposed on our society by the top 1 percent, perhaps the greatest is this: the erosion of our sense of identity, in which fair play, equality of opportunity, and a sense of community are so important. America has long prided itself on being a fair society, where everyone has an equal chance of getting ahead, but the statistics suggest otherwise: the chances of a poor citizen, or even a middle-class citizen, making it to the top in America are smaller than in many countries of Europe. The cards are stacked against them. It is this sense of an unjust system without opportunity that has given rise to the conflagrations in the Middle East: rising food prices and growing and persistent youth unemployment simply served as kindling. With youth unemployment in America at around 20 percent (and in some locations, and among some socio-demographic groups, at twice that); with one out of six Americans desiring a full-time job not able to get one; with one out of seven Americans on food stamps (and about the same number suffering from “food insecurity&rdquo

In recent weeks we have watched people taking to the streets by the millions to protest political, economic, and social conditions in the oppressive societies they inhabit. Governments have been toppled in Egypt and Tunisia. Protests have erupted in Libya, Yemen, and Bahrain. The ruling families elsewhere in the region look on nervously from their air-conditioned penthouses—will they be next? They are right to worry. These are societies where a minuscule fraction of the population—less than 1 percent—controls the lion’s share of the wealth; where wealth is a main determinant of power; where entrenched corruption of one sort or another is a way of life; and where the wealthiest often stand actively in the way of policies that would improve life for people in general.

As we gaze out at the popular fervor in the streets, one question to ask ourselves is this: When will it come to America? In important ways, our own country has become like one of these distant, troubled places.

Alexis de Tocqueville once described what he saw as a chief part of the peculiar genius of American society—something he called “self-interest properly understood.” The last two words were the key. Everyone possesses self-interest in a narrow sense: I want what’s good for me right now! Self-interest “properly understood” is different. It means appreciating that paying attention to everyone else’s self-interest—in other words, the common welfare—is in fact a precondition for one’s own ultimate well-being. Tocqueville was not suggesting that there was anything noble or idealistic about this outlook—in fact, he was suggesting the opposite. It was a mark of American pragmatism. Those canny Americans understood a basic fact: looking out for the other guy isn’t just good for the soul—it’s good for business.

The top 1 percent have the best houses, the best educations, the best doctors, and the best lifestyles, but there is one thing that money doesn’t seem to have bought: an understanding that their fate is bound up with how the other 99 percent live. Throughout history, this is something that the top 1 percent eventually do learn. Too late.

Read More http://www.vanityfair.com/society/features/2011/05/top-one-percent-201105?printable=true¤tPage=all#ixzz1LiqlGoSG

Act Now: Industrial Farms Want to Make Taking Photos Illegal

Industrial/factory pork, poultry, turkey and beef farms are well known for the terrible manner in which they raise animals and process the meat. Too often their misdeeds have been captured in photos and video by undercover persons that do not agree with what they do.

I recall the farm that hung pigs by a chain off a tractor lift and shot them when they were sick. They said that was an okay way to dispose of them. Yes, a bullet is a swift way to kill a sick animal, but to hang them off a tractor first. Give me a break.

I am sure Slow Food and others will be on the short sitck of this legislation as big ag pushes it through and soft governor’s sign it.

The following is from Slow Food. the second article is from The Miami Herald

Imagine if taking photos of farms were illegal — and

the photographer was subject to fines and possibly

jail time. If Big Ag got its way, that’s exactly what

would happen. Right now they’re pushing legislators

in Minnesota, Florida, and Iowa to criminalize taking

photos or videos of their facilities.[see note 1]

I guess industrial agriculture has something to hide.

Maybe it’s the way factory farms mistreat workers,

animals, and the environment.

| The clock is ticking — Iowa's legislation could pass an important hurdle as soon as next week. If we can raise a big enough stink, we can stop this state-based legislation from spreading nationwide. But that’s not all. We don't just want to stop Big Ag's attempt to restrict consumers' right to know — we also want to use this as an opportunity to lift up the good, clean and fair farmers who like consumers to come and see exactly how their food is produced. So join the |

New Kid and Same Kid + Brother

Caddo Lake, Don Henley & the Eagles

Caddo’s guardian: Music icon Don Henley says his efforts to preserve lake a ‘success story’

By LEE HANCOCK The Dallas Morning News | Posted: Saturday, May 7, 2011

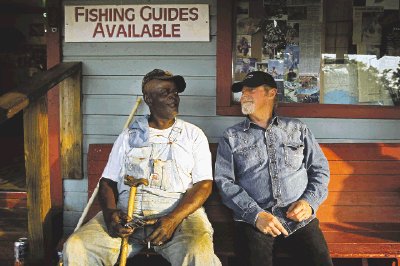

UNCERTAIN — Perched on a grimy bait-stand bench, beneath a sign that reads “fishing guides available,” a bearded man in an untucked denim shirt watches kids tumble off a dock into coffee-brown murk and boats cruise beneath the curtain of cypress.

At first glance, the sunburned man looks like any other Caddo Lake local.

It’s his baseball cap that hints Don Henley isn’t a typical lake rat. Instead of faded camouflage, the hat is navy blue, its “LIFEGUARD” logo and Red-Cross emblem framed with: “Off Duty: Save Yourself.”

The East Texas native has spent nearly 20 years and millions of dollars helping Caddo Lake residents learn to do just that — to band together, arm themselves with scientific data and go to court and Congress to protect the place that the famed rock musician calls his church.

They’ve succeeded so far. The lake where Henley caught his first fish as a young boy from neighboring Linden is a world-renowned wetland laboratory, thanks to Henley’s Caddo Lake Institute.

“It’s a success story in that we’re still here,” Henley says. “And we’re making progress, albeit slowly.”

Despite a century of exploitation of the lake, black bears and bobcats still haunt its remote corners. Alligators and otters and mink glide through its labyrinth of sloughs. Bald eagles and blue herons, egrets and ibis soar overhead.

Biologists hail Caddo as Texas’ most diverse freshwater ecosystem and one of North America’s finest bald cypress swamps. The lake is a place that locals believe has a near-mystical power to help people find or lose themselves.

“You can more or less leave your troubles on the land and escape back into the cypress swamp,” says resident Robert Speight. “You get back far enough and time stands still.”

‘Given us the tools’

Scientists from around the country visit regularly for meetings sponsored by Henley’s institute. Recently, several dozen gathered in a community center near the lake to share Speight’s home-cooked barbecue and discuss research with him and the other locals whom Henley dubs “indigenous scholars.” As always, the visitors marveled at the locals’ engagement. The locals credit Henley’s institute for distilling their fierce contrarianism and love for Caddo Lake into a force.

“They’ve given us the tools,” Speight says of the institute, “to handle things ourselves.”

Decades of debate over whether Caddo’s water and surrounding lands should be tapped for industrial or economic development have subsided. Former combatants have joined forces with the nonprofit institute to ensure the lake’s future. The region celebrated when the institute won a 14-year campaign to turn a lakeside Army ammo factory into the Caddo Lake National Wildlife Refuge.

Yet the 63-year-old singer isn’t standing down. Though just back from an Eagles concert tour in Asia and commuting from his Dallas home to Nashville, Tenn., to finish a solo album, Henley is beginning a fundraising campaign for his institute. He also headed recently to Washington to lobby for the lake and the music industry.

In between, Henley brought two of his three children to Caddo Lake to fish beneath ancient moss-draped cypress trees. Henley says he’s passing on what he learned from his late father — that it’s essential to slow down and spend time in such wild places. He wants his kids to understand that preserving such natural wonders are do-it-yourself operations.

Watching his 11-year-old daughter haul in bream with a cane pole, Henley says he believes that she and her siblings understand. “I want them to be stewards of this lake after I’m gone.”

Birth of activism

Henley’s activism began when he heard about a proposal to put a barge canal through the lake and its main tributary, Big Cypress Bayou. Then living in California, Henley had just immersed himself in a campaign to stop development at Walden Woods near Concord, Mass., the refuge of the 19th-century writer Henry David Thoreau.

Even after Henley became a celebrated member of the Eagles, the Caddo Lake area remained his home ground.

His parents met in a riverfront honky-tonk just upstream in Jefferson. Caddo Lake was a spiritual refuge for Henley’s dad, a Depression-era child of East Texas dirt farmers and owner of an auto parts store.

Throughout Henley’s boyhood, his father often woke him before dawn to fish the lake. There, Henley recalls, he got earliest glimpses of artistry, courtesy of the foul-mouthed steelworker who was his father’s fishing buddy. Henley’s awe is palpable as he describes that rough man’s gift with a fly rod.

When Henley heard that Caddo Lake was under threat, he recruited a Colorado lawyer friend, Dwight K. Shellman, to visit Texas in December 1992. The two men then created Caddo Lake Institute.

In late 1993, thanks to the institute’s work, Caddo Lake became the 13th U.S. site designated a “wetland of international importance” — joining the Everglades and Chesapeake Bay — under the Ramsar Treaty. The 1971 treaty, with 160 participating countries, is aimed at protecting wetlands and ensuring their wise use.

Shellman moved part time to Caddo Lake and forged bonds with residents. The lawyer also coordinated Caddo Lake’s first substantive scientific research.

“Before that, nobody was studying the lake,” said Roy Darville, the institute’s biologist and a professor at East Texas Baptist University.

Shellman convinced Henley of the need to make Caddo Lake a living laboratory and recruit government and academic researchers. Even so, Henley recalls thinking Shellman was crazy when he proposed asking the Army to transfer its mothballed ammunition plant on the lake’s south shore to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service for a wildlife refuge.

Shellman had a wily ability to find openings and allies. Henley had star power. They made repeated pilgrimages to Washington.

“Once he’d established what the target was or who the target was, then he would bring me in,” Henley recalls. “We used everything at our disposal — every concert, any chance.”

Years of work

Getting the refuge took years of prodding and a showdown with businessmen who wanted to turn the Army plant into an industrial park. There was also a legal battle to stop the city of Marshall from selling lake water to a power plant. That ended with an institute victory after both sides spent a total of more than $1 million on legal fees.

Some in Marshall tried to paint Henley as an outsider enjoying a rock star’s hobby. That bemuses Henley.

“I’ve put in too much blood, sweat and tears for this to be a hobby. A hobby is supposed to be fun,” he says. “It’s rarely fun because there’s always something to worry about; there’s always somebody trying to mess with the lake.”

When the federal wildlife refuge finally opened in September 2009, Shellman was retired and too debilitated from Lou Gehrig’s disease to attend the dedication.

His photograph is displayed prominently at the refuge’s Ramsar education center in a restored guard-house. Beneath Shellman’s photo is the only mention of Henley around the lake. His name is in tiny type in a list of supporters of the guard house restoration.

Though he owns lakefront property and visits regularly, Henley cherishes his low profile.

“It’s not about me,” he says. “It’s about the work, and it’s about the place, and it’s about the people who live here and recreate here.”

The institute’s director, Austin environmental lawyer Rick Lowerre, is leading a regional water planning process aimed at ensuring adequate environmental flows for Caddo Lake. That effort is considered a statewide model for water planning.

One of the institute’s targets is the giant salvinia, an invasive Brazilian water weed that first appeared at Caddo Lake in 2006. A Texas A&M study there involves breeding a species of weevils that gobble the plant.

Alarming levels of mercury have been documented in the lake’s food chain, including the highest level recorded in any snake on the planet. Much of the mercury has been traced to exhaust from nearby coal-burning power plants.

When the Eagles’ Asian tour stopped in Beijing, Henley met with researchers developing cleaner-burning coal plant technologies. Later this year, he plans to meet with the head of the large U.S. power company that is partnering with the Chinese.

“Sound science may be our saving grace,” he says. “But oftentimes in Washington — and certainly in Texas — politics trumps science.”He is cautiously optimistic, but the challenge is a big one: finding a balance between human demands and environmental realities.

“What Will Rogers said about land back in 1930 can be applied to water,” Henley says. “They ain’t making any more of it.”

Kids on the Farm

Say cheese!